Obscure history and archaeology of the Salt Lake City area (plus some Utah West Desert) as researched by Rachel Quist. Follow me on Instagram @rachels_slc_history

07 June 2022

La France Apartments demolition update

17 May 2022

Demolition of the Historic La France Apartments

- La France Apartments Slated for Demolition | 16 September 2021

- Current status of some SLC demolition permits | 03 November 2021

- La France Apartments Burning | 10 March 2022

10 March 2022

La France Apartments Burning

A demo permit was recently filed with the City so this was inevitable. (meaning, SLC buildings that are abandoned and slated for demolition often catch fire in SLC, this is just an example of a long history of fires in historic buildings).

31 December 2021

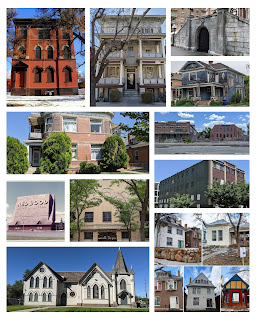

Some historic buildings that were saved from demolition in 2021

These are some of the historic buildings that were saved from demolition in 2021! Visit @demolishedsaltlakepodcast for some buildings that were lost this year.

Descriptions clockwise from the upper left corner:

1. Hyland Exchange, 847 S 800 E SLC. It will be converted to housing. But, 2 Victorian homes were demolished.

2. The Annex Apts, 150 E South Temple SLC. A project plans to rehab the Annex but it also demolished the Carlton Hotel next door.

3. Elks Block, 139 E South Temple SLC. Most buildings will be preserved, the Elks building will be renovated, the Elks tunnel entrance will be partially preserved.

4. House at 235 S 600 E SLC. The owner plans to add an addition to the back of the house and start repairs and rehab of the rest of the house.

5. Utah Pickle and Hide buildings at 737-741 S 400 W SLC. Some selective demolition has occurred but the main buildings are planned to be rehabbed.

6. Central Warehouse at 520 W 200 S SLC. The back half of the building has been demolished; the remaining front is to be integrated into a multi-use development.

7. These 5 houses on 200 East were subject to a rezone application which would result in their demolition. The rezone was not approved, and the houses are now being repaired.

8. 15th Ward Chapel at 915 W 100 S SLC was listed for sale which could have resulted in demolition; it was purchased by the Utah Arts Alliance and is now known as the Utah Art Castle.

9. Redwood Drive-In and Swap Meet at 3688 S Redwood WVC was proposed for demolition for a large housing project. Largely due to the backlash from the swap meet community the prospective owner decided to cancel the sale and development.

10. University of Utah’s Einar Nielsen Fieldhouse has undergone a seismic retrofit and will be converted to a theater.

11. Apt complex at 230 West 300 North SLC will be preserved while the area behind it will become additional multi-family housing.

It is important to note that only 2 of these projects had local historic preservation requirements for the property. All the others were only preserved because the owners desired it.

A big thanks to the owners, architects, engineers, and builders who all worked to keep some of Utah’s history standing.

16 September 2021

La France Apartments Slated for Demolition

|

| The La France Apartments (originally called Covey Flats) at 246 W 300 South Salt Lake City. Image from UDSH. |

Demolition is planned for the La France apartments at 246 W 300 South. The current owner, the Greek Orthodox Church, plans to demolish the buildings for a new complex consisting of apartments, hotel, parking garage, shops, and restaurants.

The La France was one of the first urban apartment buildings constructed in SLC. Boarding houses, hotels, and rowhouses had been used for multi-person housing for decades but this new style of a walkup multi-story apartment which included individual kitchens and bathrooms was a new building type for SLC in the early 1900s.

The first apartment house built in SLC was the now demolished Emery-Holmes apartment building constructed in 1902 which was located where the Eagle Gate Apartments are now situated at 109 E South Temple.

The La France was built in 1904 and was the first collaboration among Covey Investment Co, architect David C. Dart, and builder Charles Andrew Vissing. This group built about 20 apartment buildings in SLC, many of which survive today including the Kensington, Princeton & Boulevard, The Covey, and Hillcrest buildings.

The La France is unique as it includes rowhouses in the back of the main buildings. All apartments provided modern conveniences including steam heat, hardwood floors, gas range, refrigerator, colored tile bath with shower, tile drainboard in the kitchen, and janitor service.

Like today, Salt Lake City was experiencing a population

surge in the early 1900s. The La France was built to accommodate the

white-collar worker of the railroad, mines, and other industries. Common

occupations were railroad clerk, salesman, engineer, bookkeeper, and draftsman.

Although the La France was built in the emerging Greektown it did not serve the housing needs of the Greek community. The 1910 and 1920 censuses show no Greek or Italian immigrants living in these apartments. Rather, all La France dwellers were of Northern European decent indicating a that the Greeks and Italians living in the neighborhood were discriminated against for housing at the La France.

Covey Investment Co owned the building until 1981 and ownership ultimately transferred to the Greek Orthodox Church.In 1989 and 1992 the La France had the opportunity to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places and by default become a local SLC Historic Landmark site (those rules have since changed) but the owners objected to its listing on the local historic register. It was included in the 2016 Warehouse District National Register listing so it would qualify for tax credits if it was subject to historic rehab but there are no historic legal protections on the buildings.

Sources: SL Trib 1904-01-27; Des News 1906-09-01; SL Trib 1937-05-25; SL Trib 1980-06-20; UDSH site file, census records.

12 July 2021

The Stockade: SLC's Officially Sanctioned Red-Light District, 1908-1911

In 1908, most of SLC’s Block 64 in the emerging GreekTown (see previous post) became SLC’s new red-light district known as The Stockade.

Prostitution was not new to SLC and an unofficially controlled form of prostitution (where sex workers were arrested, paid a monthly fine, and were set free to do it all again) was practiced in SLC since 1870.

What made the Stockade different was that it was officially sanctioned, developed, and protected by the Mayor, City Council, and Chief of Police; and it was run by a single Madame. That woman was Dora Topham, more popularly known as Belle London.

SLC Chief of Police, Thomas Pitt, first suggested formally regulating prostitution in his annual report of 1907. While the newspapers and anti-vice groups initially dismissed the idea, mayor John S. Bransford and the City Council (most were members of the American political party) quietly started implementing the plan.

Bransford said, at least publicly, that moving the red-light district from Commercial Street (now Regent Street) where it had existed since the 1870s would allow the downtown business district to thrive in more respectable endeavors. Privately, Bransford and some City Council members had plans in the works to profit from the move.

Block 64 (100-200 S / 500-600 W) was chosen for the Stockade as it was near the railroad tracks, away from schools, and had existing utilities and infrastructure within the inner block: namely Boyd Court and Carter Terrace.

In addition, the neighborhood was transforming into GreekTown and “most of the better class of residents were leaving” as more Greeks, Italians, and Japanese were moving in. Thus, according to SLC’s leadership the new immigrants had already destroyed the respectable nature of the neighborhood and establishing the red-light district would not harm it further.

|

| Constructing the cribs in 1908.On 200 South looking into the interior of the block, from UDSH |

|

| Constructing the cribs in 1908.On 200 South looking into the interior of the block, from UDSH |

Topham was described as “an extremely clever woman” and brought in from Ogden where she was well known for being a Madame. More about her later.

The Citizens Investment Co began construction in the summer of 1908. A 10-foot wall surrounding the Stockade was built with entrances at the north and south sides of the block. Existing houses were converted into brothels and rows of new cribs were built. New buildings for saloons and stores were built primarily along 200 South, including the soon to be demolished Citizen Investment Co building at 540 W 200 South.

The existing residents of Block 64 opposed the new Stockade and they organized as the West Side Citizens League and made formal complaints to the City Council. They filed a lawsuit to stop the opening of the Stockade and won with an injunction being issued, which was then completely ignored by the City.

In Dec 1908 the Stockade formally opened and pressure was placed on the Commercial Street Madams to move locations. A few of the Madams moved to the Stockade, a few closed shop and left town, and a few persisted and remained open on Commercial Street through the Stockade years.

Those opposing the Stockade eventually won a legal battle that stuck and Topham was sentenced to 18 years of hard labor for inducing a woman into prostitution (later reversed by the Utah Supreme Court). In response Topham abruptly closed the Stockade in Sept 1911 and sold her property, eventually moving to California.

The occupants of the Stockade either returned to Commercial Street or remained on the west side of 200 South. Commercial Street remained a red-light district until the late 1930s and 200 South remained one until the late 1970s.

|

| Map of the Stockade from Jeffrey Nichols book Prostitution Polygamy and Power. Color highlights added for clarity. |

|

| Overlay of the Stockade from 1911 Sanborn onto modern Google Map 2020. Green show modern landmarks; Yellow show Stockade features. |

09 July 2021

The Development of Block 64 into SLC's GreekTown

When SLC was first platted in 1847 the 10-acre blocks were laid out in a grid pattern with Block 1 situated at SE corner of the city, at what is now 800-900 South and 200-300 East. Block 64 is located at what was then the western edge of the City.

Lots were divided among those early Mormons with the widow Nancy Baldwin’s family getting 2 lots on Block 64, the entire southwest quadrant of the block. When George W. Boyd married into the Baldwin family (he married 3 of Nancy’s daughters) those lots and others that he eventually purchased became known as the Boyd property.

For several decades Block 64 remained as much of the rest of SLC– sparsely spaced adobe homes with each house having room for gardens, orchards, and farm animals.

|

| Bird's eye view of Salt Lake City, Utah Territory 1870. From LOC. |

After more than 40 years of owning property on Block 64, George started selling his property to his children (and others) in the 1890s. William B. Boyd built tenements behind the adobe homes and named the area Boyd Court, which was later called Boyd Ave when the area became known as the Stockade.

Other property owners on Block 64 and surrounding areas were also building rental units and commercial spaces in the 1890s; notably A. R. Carter who built the large Carter Terrace on the north central side of Block 64 that was later converted to brothels (more on that later).

The 1890s also brought city utilities such as electricity, water lines, and sewer line to Block 64; paved streets came in 1902.

In the 1890s the property owners were still largely Mormon with about half of the buildings on Block 64 being older adobe homes. But some new elements, such as the Westminster Presbyterian Church, had started moving in and the neighborhood had begun its transformation.

|

| Salt Lake City, Utah 1891. From LOC. |

Between 1900-1905 Block 64, and other surrounding areas, developed rapidly into a Greek enclave mostly due to Greek labor agents such as Leonidas Skliris and Nicholas Stathakos who brought in their countrymen to work the nearby mines and railroad.

In 1905 the Greek community had built its first church in SLC- the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church located at 439 W 400 South (now demolished), the precursor to today’s Holy Trinity Cathedral built in 1923 (279 S 300 West).

|

The first Greek Orthodox Church located at 439 W 400 South (now demolished) in 1908. From UDSH. |

|

| Greek wedding of Magna residents Angelo Heleotes at SLC’s first Greek Orthodox Church, 1915. From UDSH. |

By 1908 the west side of 200 South had become known as GreekTown and, not coincidentally, SLC leadership decided to move the Red-Light District to Block 64 to try and break up the enclave of “undesirable” Greeks congregating in that area (among other reasons). More on that later.

The 1910s and 1920s were the peak of SLC’s GreekTown. Much like the rest of SLC’s downtown and other ethnic neighborhoods of SLC, the 1950s and 1960 saw decline through the elimination of public transportation and the emphasis on building up the suburbs.

|

| Open Heart Coffeehouse in SLC GreekTown at 548 W 200 South; Proprietor Michael J Katsanevas is standing, ca 1920. From UDSH. A note on this image: This photo shows the Citizens Investment Co Building when it was used as a Greek coffeehouse (later the Café Orbit/Metro Bar) and soon to be demolished. Thanks to a great-granddaughter of Katsanevas for updated and correct info! |

Sources:

- For more about the first platting of SLC: Cartography and the Founding of Salt Lake City by Rick Grunder and Paul E. Cohen. UHQ V87 N3, 2019.

- For more about Greeks in Utah: Toil and Rage in a New Land: The Greek Immigrants in Utah by Helen Papanikolas, UHQ V38 N2, 1970.

29 June 2021

Demolition of the Last Remaining Building from “the Stockade”

|

| Citizen Investment Co building at 540 W 200 South SLC, June 2021. |

This building at 540 W 200 South will be demolished as part of the Cinq Apartments, the same construction project that plans to preserve most of the nearby Central Warehouse building (see previous post).

This unassuming building has a sordid history and is the

last remaining building from “the Stockade,” Salt Lake’s officially sanctioned red-light

district built and managed in 1908 by Dora Topham, aka the Madame Belle London.

The building is named the Citizens Investment Co building

because that was the legal entity that was established by Dora Topham to

purchase the land, build the stockade, and manage other matters.

There are a lot of stories associated with this building and

plot of land. Before this building was

constructed in 1908 it was the location of George W. Boyd’s adobe house- he

built Boyd’s Pony Express Station in Utah’s West Desert, which remains today as

one of the best-preserved Pony Express Sites.

George was a Mormon polygamist with 3 wives and 15 children.

Exploring how Boyd’s property and the surrounding blocks morphed

from small Mormon Pioneer adobe houses into GreekTown should be interesting.

This also seems to be a good time to explore the life of

Dora Topham; she made quite the impact in Ogden but was only in SLC a few

years. Plus, she is the namesake for

London Belle Supper Club.

And then there is the red-light district itself. What did it

look like (and smell like?) and what was it like for the women who lived and

worked there. What did GreekTown think

of their new neighbors?

What other things interest you about this property and the

stories around it? Maybe I will find out for you during my deep dive and share

more interesting stories about SLC’s past.

There will likely be a few interesting posts to come out of

this topic so stick around.

In the meantime, swipe to read the historical marker

attached the building. I always stop and read the plaque!

28 June 2021

Blue Eagle Poster in SLC's Warehouse District 1933

These posters are not the National Rifle Association; they are of the short-lived federal agency the National Recovery Administration, which was a New Deal program during the Great Depression.

The NRA only lasted between 1933-1935 but had a profound impact. Some of the goals were to protect workers and ensure fair wages were paid.

Companies that signed the agreement received the “Blue Eagle” emblem to display. Some of the requirements were:

- Hours of workers capped at 40 hours per week.

- Wages raised to set standards.

- Don’t employ child labor.

- Don’t profiteer.

- Deal only with others who earn the Blue Eagle

SLC and Utah companies eagerly signed up for the program as a show of patriotism. Not everyone followed the rules but even the appearance of a violation was problematic.

In Nov 1934 the NRA alleged that Myers Cleaning and Dyeing company of SLC violated some of the provisions and required the company to surrender its Blue Eagle. The very next day a large advertisement in several newspapers printed the signed statement from 40 Meyers employees stating that the company was in fact complying with all codes and it was an issue with one of their nightwatchmen. Meyers Cleaning stated they would be exonerated in a fair and just hearing.

The revoking of Meyers Cleaning’s Blue Eagle had implications beyond SLC. In Price, M. F. Meyers who owned the Acme Cleaners and Tailors of Price, needed to clarify that he was not connected with the Meyers Cleaning company of SLC and that his establishment strictly adheres to all provisions of the Blue Eagle code.

Read more about the NRA, the Blue Eagle, and its effect on Utah’s Labor Unions in the Utah Historical Quarterly 1986 article “The Economics of Ambivalence: Utah’s Depression Experience” by Wayne K. Hinton. The UDSH has made these freely available on issuu.com.

A Sports Note: The NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles were named after this Blue Eagle symbol in 1933.

Sources: UHQ 1986 The Economics of Ambivalence; SL Trib 1933-08-23; Bikuben 1933-Aug-30; SL Trib 1934-11-14; SL Trib 1934-11-15; Sun Advocate 1934-11-15. Images of Central Warehouse are from @utahhistory_collections. News clipping is from Bikuben 1933-Aug-30.

|

| Central Warehouse 520 W 200 S SLC. Note Blue Eagles in the windows. From UDSH. |

|

| Detail of left (west) window of Central Warehouse. |

|

| Detail of right (east) window of Central Warehouse. |

|

| News clipping is from Bikuben 1933-Aug-30 (Bikuben was a Scandinavian newspaper in SLC) |

27 June 2021

Central Warehouse Building at 520 W 200 South

The Central Warehouse building is one the few remaining historic structures in the heart of Salt Lake’s Old GreekTown; however, the building is not specifically associated with the culture or Greek people of GreekTown.

What remains of the Central Warehouse (520 W 200 S) was actually the last addition to the huge warehouse complex that was initially constructed ca. 1910 at ~160 S. 500 West (now demolished; current site of Alta Gateway Station Apts).

The original section of the warehouse along 500 West was built in 1910 for the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Company, a billiard equipment company based in Chicago. It was then acquired in 1917 by Charles Tyng for use as a warehouse. Charles Tyng died suddenly in 1924 and Central Warehouse Company acquired the property during the settlement of his estate.

Central Warehouse Company was founded by George E. Chandler who was a prominent business and real estate man in Bingham and Salt Lake. It seems that George immediately handed off management of Central Warehouse to his daughter, Bess Chandler Rooklidge, as she was listed as manager in the 1925 city directory under the name “B C Rooklidge” and she was identified as the owner by 1927.

In 1925 Bess was 42 years old, married, and had one 13-year-old son. Before she married, she graduated from Wellesley College and had traveled throughout Asia with her father. Bess’s husband may not have liked his wife’s new career because in 1927 he moved out of the family house and into the Alta Club; Bess identified herself as divorced soon after.

It was under Bess’s management that the Central Warehouse expanded and built the addition now remaining at 520 W 200 South. The warehouse was built in 1929 by contractor Hector M Draper of fire-proof reinforced concrete and it featured a brick front with ornamental colored tile surrounding the doorway and a large mezzanine inside which was used for offices.

Central Warehouse moved their office operations to the new building in Jan 1930. With their new addition and their old building, Central Warehouse Company became one of the largest storehouses in the Intermountain West.

Around WWII, Bess retired and the management of Central Warehouse was taken over by her son J. Chandler Rooklidge. The company dissolved soon after his death in 1975.

The original warehouse section along 500 West was demolished in the 1980s leaving only the 1929 addition still standing. The Central Warehouse was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. (I think the plaque should be updated to reflect Bess’s contribution instead of her father’s ownership).

The Cinq apartment construction project plans to prominently incorporate the 1929 warehouse into its design and build around it. A small portion of the rear will need to be removed but most of the structure will be kept intact. The Central Warehouse does not have any local historic protections, so the preservation of the building is not required for the developer.

|

| Proposed Cinq Apts. Note Central Warehouse in center. Images from SLC Planning Commission Report. |

|

Original section of the warehouse in 1912 as the |

|

| New addition Central Warehouse, 1933. From UDSH. |

|

| Interior of 3rd floor, 1933. From UDSH. |

|

| New addition and original warehouse 1939. From UDSH. |

|

| Central Warehouse 1979. From UDSH. |

|

| Detail of front entrance, ca 1997. From UDSH. |

|

| Front entrance of Central Warehouse, 2021. |

|

| City Directory advertisements from 1925 (top) and 1926 (bottom). |

|

| Bess C. Rooklidge, 1924. From her passport photo on Ancestry. |

|

| National Register plaque currently on the Central Warehouse, 2121. (I think it should be updated to reflect Bess’s contribution instead of her father’s ownership.) |