|

| Old Veterans Hospital in 2022, as Condos |

|

| Veterans Hospital ca 1930s. Image from UDSH |

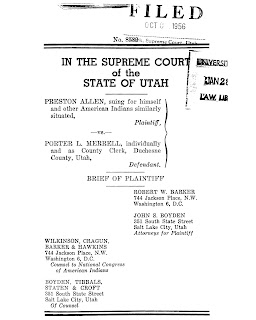

This is the old Veterans Hospital at 401 E 12th Avenue (roughly 12th Ave and E Street) in Salt Lake City is now the Meridien Condos at Capitol Park.

Built-in 1932 in a neoclassical style, this 5 ½ story brick building was originally set back from the street on a steep hill and surrounded by park grounds. A smaller 3-story annex was added in 1939.

The newly created Veterans Administration (VA) recognized a need for a hospital in SLC to care for WWI and Spanish-American War veterans Architectural plans were drawn up in 1930 and site selection began.

Originally it was thought that the VA hospital should be located close to Fort Douglas but the VA decided on a residential area high on the North Bench (the Avenues) which provided cooling canyon breezes and was situated above the city smog.

|

| Postcard showing the Salt Lake City Veterans Hospital |

|

Postcard showing the Salt Lake City Veterans Hospital

|

More than 3 city blocks were purchased and construction was completed in June 1932. The first patient, WWI vet

Oliver J. Hunter, was admitted on July 1, 1932. Once fully opened, the hospital

provided beds for 104 patients.

Built during the Great Depression, the hospital was seen as

a method to provide good jobs to hard-hit Utahns, both during and after

construction. Later the Works Progress Administration (WPA) provided labor

tending to the grounds surrounding the hospital.

The hospital boasted state-of-the-art facilities including

dentist care, an x-ray department, surgery, dining rooms, and a dietary kitchen. During WWII, the focus of the Veterans Hospital became

vocational rehabilitation and physical therapy.

|

Veterans Hospital group, Christmas Day 1942. Image from UDSH.

|

Returning Soldiers from WWII greatly outpaced the SLC Veterans

Hospital and the US Army opened the much larger Bushnell Hospital in Brigham

City in 1942. And in 1946 SLC was approved for a new VA facility with

construction work starting in 1950 on part of the Fort Douglas Military

reservation; this new VA Hospital was opened in 1952 and is the current main

campus of the SLC VA hospital system at 500 Foothill Blvd.

In 1962 the old Veterans Hospital in the Avenues neighborhood was closed to

patients and was soon declared surplus. In December 1964 the property was purchased

by the LDS Church and used the old hospital as an annex to its Primary

Children’s Hospital. The LDS Church sold it in 1987 to IHC Hospitals Inc and

when the new Primary Children Hospital was built in 1990.

Most of the land (28 acres) surrounding the old Veterans

Hospital was subdivided and sold to developers. The hospital and a few

surrounding acres were retained and the building was used intermittently but was

primarily vacant for 16 years.

In 2004 it was purchased by Pembroke Capitol Park and

converted to luxury condominiums through historic adaptive reuse, done by Hogan

Construction at a cost of $20M. The interior was gutted, an underground parking

structure was added, and the exterior was preserved. The condo conversion was

completed in 2008.

In 1988 the building was shown in the movie Halloween 4 as Smiths

Grove Sanitarium.

Of Note:

It is likely that the Veterans Hospital on 12th

Avenue was segregated. The Tuskegee Hospital for Sick and Injured Colored World

War Veterans in Tuskegee Alabama opened in 1923 and was the only Black Veterans

hospital until 1954.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the Veterans Administration

allowed hospitals to choose their segregation status based on local and

regional practices, which for Salt Lake City would mean Black Soldiers would be

in a separate ward or not allowed at all. My guess is the latter.

President Truman desegregated the US military through

Executive Order 9981 but the VA kept most hospitals segregated in some form

through 1953. On July 28, 1954, the VA formally announced that segregation had been

eliminated at all VA hospitals.

So far, I’ve only seen white men as patients in the 1940

Census. Write a comment if you know of any specifics on the SLC Veterans

Hospital policy on segregation.

Source: History of the VA in 100 Objects: number 11. https://www.va.gov/HISTORY/100_Objects/Index.asp

Sources:

- Salt Lake Telegram Nov 6 1931

- Salt Lake Tribune July 2 1932

- Salt Lake Tribune July 8 1932

- Salt Lake Telegram July 14 1932

- Deseret News Sept 14 1932

- Salt Lake Telegram Sept 9 1933

- Salt Lake Tribune July 6 1947

- Deseret News Oct 7 2005

- Salt Lake Tribune Aug 10 2006

- Veterans Hospital NRHP File, NPS

- History of the VA in 100 Objects: number 11