In 1923, a few schoolgirls found a box of human bones in the barn of the Lund family at 127 W. North Temple, Salt Lake City. The box of bones was an open secret known by many of the kids in the neighborhood.

Herbert Z. Lund Jr. recounts the story of these skeletal remains in a

Utah Historical Quarterly article titled “The Skeleton in Grandpa’s Barn” (

UHQ V35 N1 in 1967).

Herbert Jr. states that his father, Dr. Herbert Z. Lund Sr., was a physician at the Utah State Penitentiary (at what is now Sugar House Park) and acquired the body of J. J. Morris. Morris was executed in 1912 by hanging for murder; and, in accordance with common practice his body was donated for medical purposes.

|

|

Dr. Lund intended the body to become a teaching skeletal specimen. After the anatomical dissection was completed, Dr. Lund reduced the body to a skeleton. Part of the process to create a skeletal specimen is maceration so Dr. Lund and his friend William Willis (a druggist by profession) took the remains to an open area near Beck’s Hot Springs and boiled the remains in sulfur water and lime. The final process of bleaching the bones was never completed and the bones retained a rancid odor.

Dr. Lund placed the bones in a wooden box and stored them in the unused hayloft of his father’s barn, Anthon H. Lund’s house at 127 W. North Temple (now demolished).

Dr. Lund’s children (Anthon’s grandchildren) were aware of the skeletal remains and often found ways around the locked entry to view the bones. Even the grandchildren of the adjacent neighbor, LDS apostle Matthias F. Cowley, knew of the bones. So it is not surprising that other kids got into the barn to sneak a peak at the bones of a convicted murderer.

Around 1925, Dr. Lund’s mother, Sarah, demanded that the bones be buried to keep curious people away. Dr. Lund’s son, Herbert Jr, buried the remains behind the old barn. He and his grandmother Sarah had a little graveside service where Sarah read excerpts from the LDS publication “The Improvement Era” and placed the old magazines in the grave with the skeletal remains.

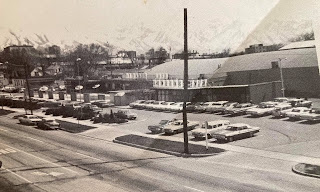

The gravesite was dug behind the barn. Sanborn maps show that this barn was demolished around 1950-1951. In the 1967 article, Herbert Jr. stated that the area of the grave was still open land but that development was happening all around.

Herbert Jr. drew a map of where he believed the gravesite to be. This location is now in an expanded parking lot of the old Travelodge Motel at 144 W. North Temple. It is unknown if construction has impacted the grave or if it is still intact below the asphalt parking lot.

One complication of this story is that there is a burial record for J.J. Morris in the Salt Lake City Cemetery, which contradicts the identity of the skeletal remains as being J.J. Morris.

However, both the Lund family history and several 1920s newspaper articles (including an interview with Dr. Lund, himself) indicate that the skeleton in Grandpa’s barn is J.J. Morris.

The burial record for J.J. Morris indicates that he is buried along with 14 other prisoners whose remains were originally interred at the old Utah State Penitentiary, which is now Sugar House Park. These remains were disinterred from the Sugar House location in 1957 when the park was built. The remains were reinterred in a small prison cemetery at the Point of the Mountain Prison in Draper. In 1987, the remains were disinterred again and reinterred at the Salt Lake City Cemetery- with several remains (identified as cremains) interred in a single grave.

So if the cemetery record is to be believed (and with all those disinterment’s it is possible that records may have been compromised) then the remains buried behind the Grandpa’s barn are not those of J.J. Morris.

Utah executed several prisoners around the same time as J.J. Morris. It is possible that the identity of the skeleton in Grandpa’s barn is actually that of another prisoner whose remains were also donated to medical science around the same time. Potential candidates for this option include Harry Thorne executed Sept 26 1912 or Frank Romeo executed Feb 20 1913.

Utah Executions 1912-1913

Sources:

- “The Skeleton in Grandpa’s Barn” UHQ V35 N1,1967

- Ghosts of West Temple, Salt Lake County Archives

- "Ray Lund, Prison Doctor" by H Z (Zack) Lund (nd) from FamilySearch

- Salt Lake Tribune 1923-11-30

- Deseret News 923-11-30

- Ogden Standard Examiner 1923-11-30

- Salt Lake Telegram 1912-05-04

- Salt Lake Telegram 1912-04-30

- The Salt Lake Tribune 1980-06-19

- Various cemetery records from ancestry, names in stone, and find-a-grave